It dropped overnight by about 2 meters and 2500 cm/s

wateroffice.ec.gc.ca

wateroffice.ec.gc.ca

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chilcotin Slide

- Thread starter IronNoggin

- Start date

IronNoggin

Well-Known Member

Pineapple Express

Well-Known Member

Incredible video

Pineapple Express

Well-Known Member

wildmanyeah

Crew Member

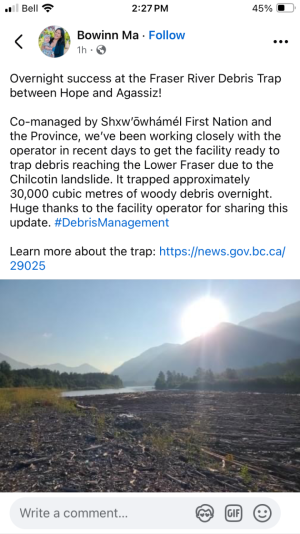

There is a debris trap between hope and Agassiz that a lot will get trapped in

IronNoggin

Well-Known Member

There is a debris trap between hope and Agassiz that a lot will get trapped in

Given the amount and sizes, they will be lucky if it doesn't tear that trap apart methinks.

Pineapple Express

Well-Known Member

The debris trap is in a side channel.

At best its catch will be minimal.

Even during freshet it " catches" a small proportion of debris that actually comes down.

Is this it? I've never known about any debris trap...thanks for sharing the info (turn on satellite view)

Google Maps

Find local businesses, view maps and get driving directions in Google Maps.

wildmanyeah

Crew Member

Is this it? I've never known about any debris trap...thanks for sharing the info (turn on satellite view)

Google Maps

Find local businesses, view maps and get driving directions in Google Maps.maps.app.goo.gl

Yes if zoom in you can see the booms that extend into the main channel, catching some is better then nothing

Pineapple Express

Well-Known Member

Yes if zoom in you can see the booms that extend into the main channel, catching some is better then nothing

I see that now, thank you. Looks like the booms extend a fair distance upstream and cover half the river or so. I wonder who funds this thing?

wildmanyeah

Crew Member

TaxesI see that now, thank you. Looks like the booms extend a fair distance upstream and cover half the river or so. I wonder who funds this thing?

Co-management agreement between Province, Shxw'ōwhámél first of its kind

Containment barriers on the Fraser River that have been intercepting debris for more than 40 years are now under a co-management agreement between the Province and the Shxw'ōwhámél First Nation.

news.gov.bc.ca

Pineapple Express

Well-Known Member

Thanks for the linkTaxes

Co-management agreement between Province, Shxw'ōwhámél first of its kind

Containment barriers on the Fraser River that have been intercepting debris for more than 40 years are now under a co-management agreement between the Province and the Shxw'ōwhámél First Nation.news.gov.bc.ca

islandboy

Well-Known Member

cohochinook

Well-Known Member

Right now I don't think salmon could pass where the slide happened. Wonder if when the levels come down it'll be possible or if they're going to have to figure out a way to transport them above?

IronNoggin

Well-Known Member

The Fraser River's trusty debris trap and its Chilcotin challenge

A trap built to keep Vancouver's shores and waterways clear of wood faces one of its biggest testsIt’s showtime for one of British Columbia’s most underappreciated pieces of infrastructure.

As the landslide-turned-dam blocking the Chilcotin River gave way Monday, it sent a torrent of water hurtling toward the Fraser Valley. But not just water.

As all that river rushed into the Fraser, it brought thousands of trees with it. Some came from the landslide that had stalled the river for days. Others were new casualties, tumbling from banks into the surging river. Fifty years ago, the logs would have ended up scattered on popular beaches or battering boats in and around Vancouver.

But thanks to a couple of long booms and a tiny island, much of the debris will end up snared next to a tiny island near Agassiz. Meet the Fraser River Debris Trap.

A trap built for driftwood

A deluge of driftwood floating down the Fraser River is not just a giant-landslide-in-the-Cariboo problem. Every year, thousands of trees fall into the Fraser and its tributaries—often when rivers rise in the spring. Dead trees that fell during the fall and winter float away when freshet waters sweep them towards the sea; live ones topple directly into the rivers as the current erodes their banks in spring. And a surprising amount of the woody debris is felled not by nature, but by humans working in BC’s vast lumber industry.

The Fraser River’s massive watershed means that across most of southwest and central BC, if a tree falls into a river, it will likely end up floating toward Vancouver. That process can take years—trees can get snagged or wash up on the banks of a river, only to float again when waters rise. Eventually, those logs pass Hope and head towards British Columbia’s most heavily trafficked bodies of water.

In the middle of the last century, so many logs floated down the Fraser during some springs that the river became unnavigable. A sternwheeler was used to pull logs from the river, but it couldn’t run during the freshet, when the bulk of the wood came down the Fraser. (Today’s it’s a museum located in New Westminster.)

In the late 1970s, those issues led the federal government, BC’s forest sector, and the province’s Ministry of Forests and Lands to create a body tasked with reducing the amount of wood floating down the Fraser.

The B.C. Debris Board’s biggest project was the creation of a “debris trap” just northeast of Agassiz. The trap, which is still in use today, harnesses the Fraser’s current and two long booms to funnel wood toward a dead-end in the river.

Although water can escape the trap through a narrow passage, a slender island hems the wood into an inlet from which it cannot escape. The trap can snare huge volumes of wood—and other debris. (See it using Google’s satellite imagery here.)

A 1986 study of the trap’s catch during one large freshet described that year’s quarry.

“The amount of debris collected was equivalent to eight football fields piled three metres deep with trees, wood chunks, branches, animal carcasses, barrels, discarded construction waste and other floating material.”

About 60% of the debris collected was “natural” in origin. Almost all the rest came from the forest industry. Debris from other industries amounted to 2% of the catch, by volume.

Every year, the trap catches huge volumes of wood—between 25,000 and 100,000 cubic metres of debris. The latter figure is the equivalent of 2,000 logging truck loads. One study estimated that the trap snares around 90% of all driftwood generated upstream.

Some springs—and weather events—bring particularly large amounts of debris down the Fraser. The 2021 atmospheric river netted the trap not only huge amounts of wood, but also recreational vehicles and portions of residential decks.

Wood has historically been salvaged, with a variety of end uses. (Even bad wood can generally be used for something; wood chips can be manufactured into particle boards while sawdust can be burned to help power their mills.)

But although seemingly simple, the debris trap isn’t free to operate. It must be maintained, and all that debris can’t be allowed to just pile up. Two decades ago, operating the trap cost more than a half-million dollars a year, with government agencies and the forest industry splitting the bill. That led to worries that the trap would be closed after coastal loggers said they couldn’t pay as much as they did previously.

Amid those concerns about costs, the Fraser Basin Council, which led the committee that operated the trap, commissioned a cost-benefit analysis that said the trap saved port authorities, transportation companies, and communities more than $8 million each year in avoided clean-up costs and repairs. The study also said the trap helped prevent marshland degradation, log spills, damage to foreshore properties, and deaths and injuries on the water.

The trap did have its critics. The leader of one local conservation group suggested the debris trap should be moved downriver to allow more logs to accumulate in salmon-rearing areas, where they help improve fish habitat. He noted that moving the trap toward Mission would also reduce the cost and environmental impacts of transporting the wood to salvage operations where it is processed.

But in general, the trap has been seen as a necessary part of keeping the river safe for boaters and free of the natural and unnatural debris generated across the Fraser’s huge watershed.

The Fraser Basin Council operated the trap for years, while campaigning for a long-term funding arrangement that would avoid the bickering that had become associated with paying for the trap. Finally, in 2011, the province took sole control over the trap, leaving it to bear its ongoing costs.

Last year, that arrangement changed, with the province signing a co-management deal with the Shxw'ōwhámél First Nation. The First Nation will take a role in the operation of the debris trap, with the agreement setting the stage for employment and business opportunities for Shxw'ōwhámél, according to a provincial press release.

“This first-of-its-kind agreement is another step forward in advancing reconciliation with First Nations by recognizing and respecting the Shxw'ōwhámél’s jurisdiction, management, authority and responsibilities within its territory,” Bowinn Ma, Minister of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness, was quoted as saying in the release.

The trap is now jointly operated by a construction company owned by the First Nation and Jim Dent Construction in Hope.

The provincial news release from last year said that the First Nation was exploring the potential of building a longhouse with the best timber salvaged.

On Tuesday, though, the challenge was not what to do with the wood, but whether the trap would have enough space to accommodate the massive—and uncountable—volume of felled trees approaching it. The Chilcotin’s floodwaters are full of huge numbers of logs. Videos show hundreds floating downriver. And most will end up funneled into the debris trap. Not all will arrive immediately. But many will, carried by the first wave of water sweeping into the Fraser Valley.

That leaves the new operators facing one of the trap’s biggest tests in the last 40 years.

If the past is any indication, the logs will end up stacked on top of one another. But whether the trap has enough capacity to deal with the incredible amount of logs floating down the river remains the big question, particularly with so many arriving within such a short time frame.

When The Current contacted the trap’s Shxw'ōwhámél operators for this story Tuesday morning, we were told meetings were ongoing.

At a press conference Tuesday afternoon, Emergency Management BC sernior regional manager Samantha Wilbur said the trap is currently at "less than 50% capacity, with approximately 50 to 70,000 cubic metres available."

Wilbur said that officials are confident that the trap will be able to continue to snare debris as water rises and said excavators were on standby to remove debris as it arrives.

The Current asked whether logs has been removed to make more room for debris as it arrives. Wilbur didn't directly answer the question, saying officials are monitoring the debris and have people to in place to remove debris as it arrives, though that activity must be done in a safe manner.

"At this time they are confident, however they do continue to monitor as new information comes out."

If the trap cannot accommodate the sheer number of logs, and if operators can’t safely make more room in the trap, much of the wood will continue their journey downstream to Vancouver—creating the same hazardous boating environment governments were eager to avoid in the past. Those extra logs will either end up on Fraser River beaches or floating away into the sea.

But If the trap—and its operators—can manage the volume, wood that would otherwise end up on beaches, or battering boats, across the Lower Mainland will end up snared next to that tiny Agassiz island.

Inevitably, the debris will have to be removed from the trap to make way for new arrivals. But just how rapidly that work must take place will be a question that only the Fraser can answer.

The Fraser River's trusty debris trap and its Chilcotin challenge

A trap built to keep Vancouver's shores and waterways clear of wood faces one of its biggest tests

fvcurrent.com

fvcurrent.com

IronNoggin

Well-Known Member

Thompson / Fraser confluence at Lytton:

wildmanyeah

Crew Member

Jamesonm

Active Member

No it managed to capture what we normally divert in a year overnight lastnight. Mission successful.Given the amount and sizes, they will be lucky if it doesn't tear that trap apart methinks.

Jamesonm

Active Member

70%The debris trap is in a side channel.

At best its catch will be minimal.

Even during freshet it " catches" a small proportion of debris that actually comes down.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 836

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 899

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K