In 2007 the ENFO initiated a program of cooperation with the Technical Committee on Compliance (TCC) of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC;

www.wcpfc.int) and the Fisheries Working Group (FWG) of the North Pacific Coast Guard Forum (NPCGF)

.

In 2008 the first ever International North Pacific IUU (illegal, unreported, unregulated) fishing workshop was held in Vancouver, Canada. Participants included numerous groups involved with fisheries enforcement, including NPAFC ENFO, NPCGF FWG, WCPFC TCC, and the International Monitoring Control and Surveillance Network. These organizations vary in membership and representation both by state and agency, and the convention provisions on monitoring control and surveillance, area, and species of interest. What the agencies have in common is the strong mandate to protect the natural marine resources of the Pacific Ocean and to combat IUU fishing.

In 2008–2009 Canada employed a newly-launched earth surveillance satellite (Radarsat 2) as a means of monitoring vessel activity in the NPAFC Convention Area. The space-based Automated Identification System (AIS) has also been employed as an additional tool for enhancing information on vessel contacts provided by Radarsat 2.

In 2010 the United States initiated a bi-weekly enforcement conference calls with participation of the enforcement agencies of the member countries on a voluntary basis. These calls are an effective real-time communication tool for coordinating enforcement patrols and updating case information.

In 2011, enforcement cooperation was successful in reducing illegal high-seas fishing. One stateless fishing vessel was spotted by an aircraft of the Fisheries Agency of Japan. This information was passed to the US Coast Guard, which responded with a patrol vessel. The vessel was engaged in unauthorized and illegal high-seas large-scale drift-net fishing. The US Coast Guard patrol vessel conducted boarding and inspection and found 30 tons of squid and 54 shark carcasses. The vessel was seized for violation of US Law.

READ MORE

In 2012, Commission members also continued successful enforcement collaboration in the Convention Area. Patrol efforts included a combined 153 ship patrol days, over 370 aerial patrol hours, and the use of radar satellite surveillance.

The combined monitoring activities in 2013 by NPAFC-related enforcement agencies included over 120 ship patrol days, more than 498 aerial patrol hours, and satellite support. Members collaborated through joint ship patrols, participation of personnel in the air and ship patrols of other member countries, and regular conference calls.

The combined multilateral efforts in 2014 resulted in

significant enforcement actions. Two suspicious vessels were sighted by US Coast Guard air patrolling. Later, one of these vessels was detained in Russia for not having a valid fishing license. In another case, a suspected high seas drift net (HSDN) vessel was encountered by a Canadian CP-140 aircraft during its patrol with two FAJ inspectors aboard. The USCG Cutter enforcement officers investigated this vessel and found that the net tube, net spreader, and 3.3 km of driftnet had been dumped over sea during the night. During investigation, half a ton of net-scarred salmon was discovered in the ship’s freezer.

READ MORE

The combined multilateral efforts by enforcement agencies of NPAFC member countries resulted in no observed high seas driftnet or IUU fishing activities in 2015. The coordinated enforcement efforts of the member countries in 2015 covered significant portions of the NPAFC Convention Area, including over 400 hours of aircraft patrols and exceeding 100 ship days. Over 500 fishing vessels were sighted and none were detected conducting illegal fishing activities. Inspection of several transhipment vessels did not indicate retention of salmon captured on the high seas. This confirms that a high level of coordination and patrol and inspection effort acts as a strong deterrent to IUU fishing.

In 2016, a suspicious fishing vessel under the People’s Republic of China flag was sighted by Fisheries Agency of Japan patrol vessel to be equipped with driftnet gear (net tube, rollers) and carried radio buoys used for driftnets within the Convention Area. A refrigerated cargo ship was sighted by the US Coast Guard patrol aircraft unflagged and with vessel name painted out within the NPAFC Convention Area in the Bering Sea. The Committee on Enforcement considered an expanding of enforcement activities by directing investigation efforts towards transshipment vessels/suppliers.

The Parties scrutinized over 2,000 fishing vessels by the Parties’ aircrafts and cutters in 2017. No high seas driftnet fishing interdiction or IUU fishing activity in the NPAFC Convention Area was sighted during the 2017 patrolling season. Member Parties also discussed the status of acceptance of the FAO Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA). This international agreement is designed to harmonize and strengthen controls and deter illicit activity by preventing illegally caught fish from entering the global marketplace. The Agreement has gone into force as of June 5, 2016. Effective and consistent application of this Agreement by nations would add a new level of deterrent by decreasing the profitability of illegal transshipment of fish at sea and in port.

Prior to 2018 ENFO regular meeting, a one-day ENFO workshop on “Emerging IUU indicators and warnings in the North Pacific Ocean” was held. The main purposes of the workshop were to identify indicators and warnings, establish an updated contact list for enforcement, investigation, and prosecution, and share information on how to combat IUU fishing.

READ MORE

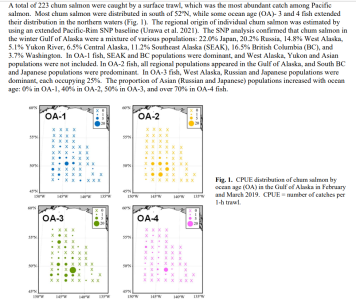

On June 11, 2018, the Chinese flagged fishing vessel, Run Da, conducting illegal high seas driftnet (HSDN) fishing in the North Pacific Ocean had been sighted by the United States Coast Guard (USCG) C-130 aircraft. After a joint boarding and inspection conducted on June 16 by the USCG and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Coast Guard shipriders, custody of the vessel was transferred from the USCG Cutter Alex Haley to the PRC Coast Guard Vessel 2301 on June 21, 2018, for prosecution. The captain of the Run Da admitted to fishing with driftnets up to 5.6 miles in length. The joint boarding team discovered one ton of squid and 80 tons of chum salmon on board. PRC Coast Guard Vessel 2301 has escorted the Run Da back to China for prosecution.

READ MORE

Prior to the 2019 Committee on Enforcement (ENFO) regular meeting, a one-day ENFO workshop on “Combating IUU Fishing and New Technologies” was held. At the workshop, there were presentations from six invited global enforcement and commercial experts. Presentations focused on overviews of contemporary approaches to Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) development, including collaborative organizations and new technologies in combating IUU fishing that could potentially be applied within the NPAFC Convention Area.

In 2020–2022, due to restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, ENFO held email meetings twice a year to coordinate patrol plans and discuss regular business matters. In addition, ten to twelve email conferences to communicate patrol outcomes were completed every year. No IUU fishing or vessel of interest sightings were reported in 2020–2022. Canada reported multiple discrepancies between AIS information transmitted by fishing vessels and the IRCS markings. The U.S. summary patrol report showed that significant Pacific salmon bycatch exists at the massive pelagic fisheries in the northwestern North Pacific Ocean. Preventing salmon bycatch was actively discussed with the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC). NPFC encouraged its members, on a voluntary basis, to report significant encounters of salmon during inspection to the SWG on Operational Enforcement, which will discuss any report on a case-by-case basis. In May 2023, at the first ENFO in-person meeting after the break, the five-year work plan to the NPAFC/NPFC Memorandum of Cooperation was adopted and joint workshops were proposed on at-sea transshipment and salmon bycatch matters.