The paradox of prevention: By avoiding the worst, we remain vulnerable to future waves of disease

The past several months have offered us, as a country, extraordinary challenges. As an epidemiologist, internist and parent, these challenges have subsumed every part of my work life and my personal life. I haven’t hugged my kids since mid-March. I have watched patients admitted to hospital with mild breathing difficulties – and have seen these same patients wheeled into the intensive-care unit 72 hours later. My colleagues have cared for married couples and have had to tell the surviving spouse of the death of their partner while on clinical rounds. I have had the gratifying experience of watching our modelling work influence policy – and have also experienced the annoyance of watching epidemiological data abused, misused and distorted in support of various political, economic and social agendas.

The challenges I have faced pale next to those faced by many Canadians, who have lost their jobs or lost their loved ones, often without the chance to hold hands or say goodbye. They pale next to the challenges faced by those who have worked at essential jobs, under pressure from employers, but without access to adequate personal protective equipment. We have watched extraordinary leadership from senior public health officials across the country, and here I would single out the clear, compassionate messaging from Bonnie Henry, Deena Hinshaw and Theresa Tam for special praise.

We have also struggled with more limited leadership in other provinces; here I would note, in particular, the failure of provincial public health officials in Ontario to act swiftly and courageously to stop the spread of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, to clearly articulate that COVID-19 was spreading in our communities in early March and to keep up with the best epidemiological evidence on important issues such as the transmission of disease by individuals with few or no symptoms.

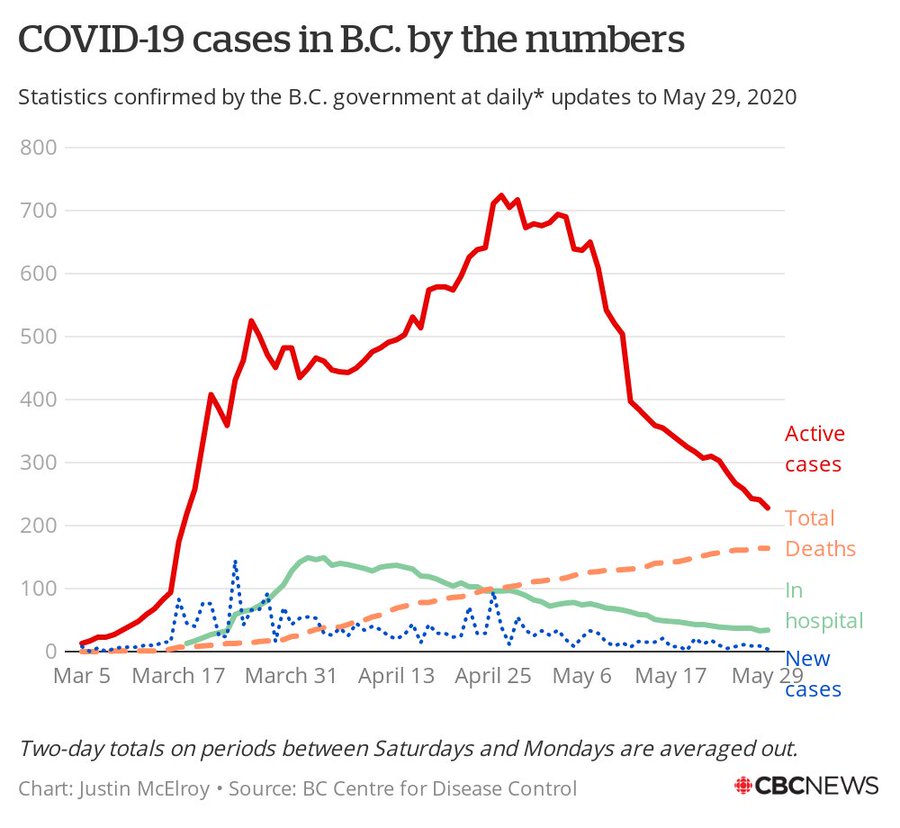

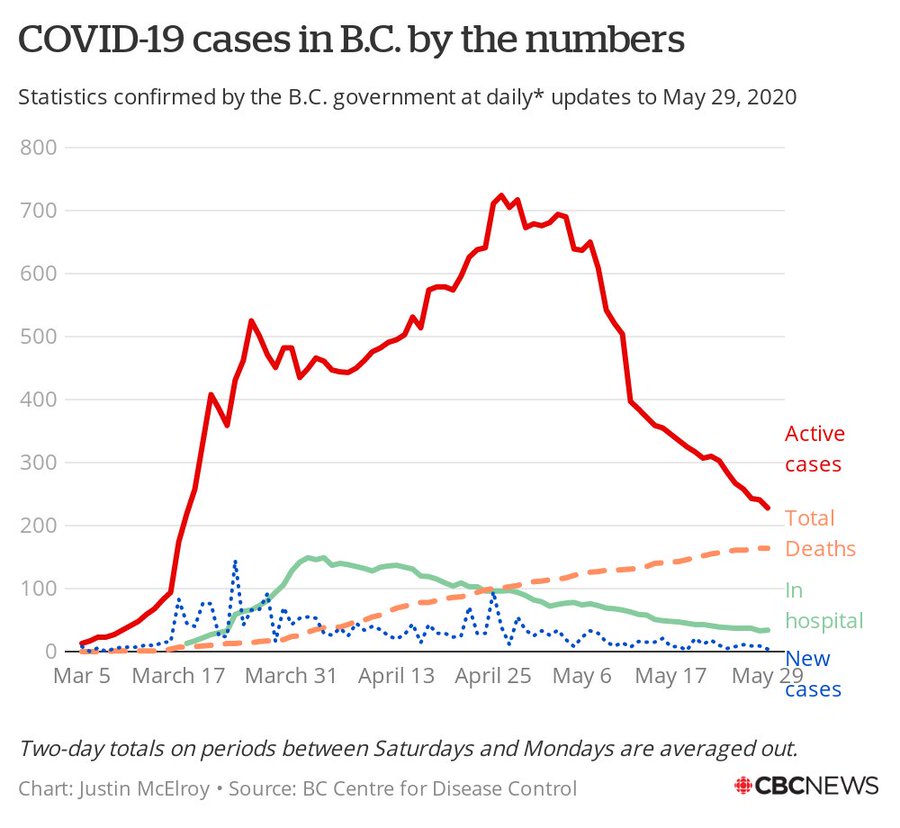

So yes, we have seen many challenges, some of which we have met and some of which we have not. My group prepares forecasts for several federal and provincial colleagues each morning, and we have documented a reproduction number for the epidemic in Canada below 1 since around May 9, 2020. This is a hopeful sign; the reproduction number of an epidemic – the number of new cases created by an old case – is an index of epidemic growth and decline, and a sustained reproduction number below 1 suggests this first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic is approaching an end in Canada.

I have been concerned about how this encouraging turn of events has been interpreted by some to mean that this wave is ending in spite of, rather than because of, the patient, selfless actions of many Canadians, who have experienced hardship, isolation and deprivation in order to distance themselves from workplaces, friends and family. In Canada, we have seen health care systems stretched and challenged but we have not witnessed the tragic overflow of intensive-care units, as has occurred in Wuhan, Lombardy, New York and Madrid.

Make no mistake: Our failure to experience these tragedies does not mean the models were wrong. Cities around the world that failed to react to approaching epidemics as promptly as Canadian cities did have experienced astounding surges in mortality: a 300-per-cent increase in New York, 75 per cent in Stockholm, 460 per cent in Bergamo, Italy, 100 per cent in London.

We reacted to approaching disaster in time to avert the worst of this first wave, though in our two largest cities (Montreal and Toronto) we still have several hundred individuals in intensive-care units.

And now we face what I will refer to as the “paradox of prevention”: By preventing widespread infection in the country we have maintained susceptibility in the population, which leaves us vulnerable to future epidemic waves. Most people who recover have immunity at least temporarily, so this assumes that people are readily infectable if they haven’t been infected yet. This is the defining paradox of public health: Our fundamental deliverable is the non-occurrence of events. Those of us who work in the field are accustomed to having our outputs taken for granted. To note one familiar example, vaccination programs are criticized because their very success means we don’t experience outbreaks. Perhaps a silver lining to this episode will be greater appreciation of what public health provides us in normal times.

But back to our avoidance of even greater tragedy in Canada in March and April. Having achieved this important success, we need to move forward with economic revitalization. I think the presentation of our choices as economic revitalization versus prevention of disease transmission is a Hobson’s choice or false dichotomy. We can’t ignore our economy, but we won’t have robust revitalization without strong surveillance systems and health-protection measures. A frightened and grieving population will not drive a strong economic recovery. In the United States, data assembled by JPMorgan Chase show clearly that declines in spending are strongly linked to levels of disease activity.

The bedrock on which revitalization rests will be public health surveillance and laboratory testing. We can’t fight an enemy we cannot see and we can’t see this epidemic without testing. The virus is a slippery foe and a study in contradictions; I call it “Schrodinger’s coronavirus” – it’s dangerous and lethal, but it causes mild illness and even infection without symptoms. It kills more than 7 per cent of Canadians with recognized infection, but gives most children a free pass.

Asymptomatic and presymptomatic infections are a Trojan horse that gives entry to congregate settings such as long-term care and retirement homes, health care facilities, prisons and food-processing plants. Once it is spreading in these institutions, it can take a terrible toll, as we have seen in long-term care facilities.

We can look around the world for successful responses to this pandemic and emulate best practices, but we can also emulate best practices in our own country. Colleagues in Newfoundland and Labrador controlled COVID-19 rapidly; they tell us to “hunt the virus” and be proactive. Colleagues in British Columbia teach us how important clear strategy and communication are in this fight. Alberta can show us how to scale up testing. And our northern territories show us how to protect isolated, remote communities. Saskatchewan has shown us how to deal swiftly with growing outbreaks to prevent geographic spread of infection.

But I do believe that our most potent weapon in this fight is testing. Work by my colleague Ashleigh Tuite shows that without aggressive testing, control measures such as contact tracing are likely to be fruitless, as we will only perform contact tracing on tested cases. If we fail to test at scale, we will miss too many additional cases for contact tracing to change the dynamics of the epidemic; it will simply be a waste of resources. If we test at scale, we can keep the epidemic in our sight and move toward economic revitalization while keeping Canadians safe.

Testing will be our eyes and ears as we move forward to open our economy, but the laboratory is a tool that needs to be used differently in different settings. We need to establish regular testing regimens for those who work in congregate settings with vulnerable individuals, especially in long-term care facilities and in hospitals. Testing in a stable and consistent way allows us to estimate the reproduction number of the epidemic and know when we are headed into exponential growth. We want to find all the cases we can – that’s how we prevent sparks from turning into forest fires. Hospitalizations and deaths are easy to see, but they are lagging indicators – instituting control policies once they are surging means we have already missed the boat. We can use non-traditional surveillance tools, too, such as web-based syndromic surveillance (using data on people’s symptoms to track disease without definitive diagnoses) and even surveillance of sewage for coronavirus levels, as is already being done in other countries. Situational awareness will keep us safe as our economy comes back to life.

We can also demand more of our country. This epidemic shows us that having laboratories with 21st-century diagnostic technology but public health information systems that depend on fax machines from 1995 will hold us back. We can demand more transparency from our leaders. As action by the public is central to disease control, it is important that the public be kept in the loop and made to feel like they are on the team. Indeed, they are the team.

We need clear, transparent benchmarks across the country on testing, on turnaround times for case reporting and contact tracing and for the reproduction numbers that will be used to determine when we need to strengthen physical distancing and when we can loosen it. We will have more setbacks; the countries with the strongest response programs in the world have all suffered them. We will, too. I’d ask you not to throw up your hands and let the virus win.

Don’t let uncertainty distract you from the mission. Uncertainty is to be expected for a disease that’s been in humans for 24 weeks. Don’t let smug professors bully you about the absence of randomized controlled-trial evidence for the management of a disease that has only existed for half a year. We can acknowledge uncertainty, and be humble about this disease, but always put the lives and livelihoods of Canadians at the forefront when we make our decisions.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opi...n-by-avoiding-the-worst-we-remain-vulnerable/