OPINION: In the king salmon debate, we’re ignoring the 8,000-pound orca in the room

By Andy Wink

Updated: 2 hours agoPublished: 2 hours ago

A pod of orcas swims in Agnes Cove on the Aialik Peninsula in Kenai Fjords National Park on Sunday, May 16, 2021. (Loren Holmes / ADN)

As we all know, chinook salmon abundance and fish size have been trending downward across Alaska for many years now. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) has studied the issue intently as part of the

Chinook Salmon Research Initiative. Regarding the key question of “what is causing low runs of chinook salmon in Alaska,” the initiative concludes the following:

Research has shown that during the recent period of poor production, marine survival has dipped below one percent. This decrease in marine survival, even in the face of some very good freshwater production in several systems, has been driving the downturn in overall adult production.

ADF&G’s research strongly suggests the problem lies in marine-stage survival. So, what’s happening? Is it overharvest by humans, climate change, or something else?

In general, human harvest rates of chinook salmon (by commercial, sport, and subsistence fishermen) have fallen sharply over the past decade, yet chinook abundance remains low.

Climate change may be at least partly to blame for declining chinook abundance. Warmer water can alter food chains and increase metabolism, making it harder for salmon to survive or flourish. However, if climate change is the primary driver of poor chinook abundance, doesn’t it stand to reason that we would see productivity trends generally improve the further north you go? That hasn’t been the case.

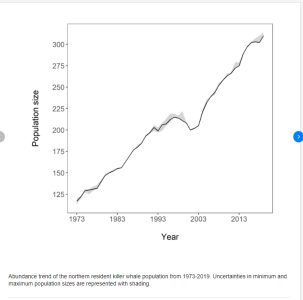

Fishermen and climate change aren’t the only challenges Chinook salmon face in their quest to survive and multiply. They are preferred prey for several marine mammal species. Given the existing research and trends witnessed over the past decade, we believe more investigation and consideration ought to be given to marine mammal predation — and this approach is strongly supported by available research. Understandably, we humans are blaming each other for the situation, but in doing so we’re ignoring the growing number of 8,000-pound orcas in the room. Consider these findings from recently published research:

• From 1975 to 2015, the biomass of chinook salmon consumed by pinnipeds and orcas increased from 6,100 to 15,200 metric tons (from 5 to 31.5 million individual salmon). Meanwhile, the decrease in adult chinook salmon harvested from 1975 to 2015 was 16,400 to 9,600 metric tons.

• Orcas consume the largest biomass of chinook salmon, but harbor seals consume the largest number of individuals.

• Estimated orca predation of adult chinook salmon increased from 1.3 million to 2.6 million individuals (per year) from 1975 to 2015. Orca predation accounted for 10,900 metric tons of the estimated 15,200 metric tons of total marine mammal predation in 2015.

• Our results suggest that at least in recent years competition with other marine mammals is a more important factor limiting the growth of this endangered population than competition with human fisheries.

• We find that widespread declines in the body size of chinook salmon over the past 50 years can be explained by intensified predation by growing populations of resident orcas that selectively feed on large chinook salmon, thus revealing a potential conflict between salmon fisheries and marine mammal conservation objectives.

Reducing marine mammal predation would be extremely challenging, from both a political and logistical perspective, but it doesn’t change the cold hard math. Seals and orcas consume far more king salmon than humans and are doing so at an increasing rate, making marginal reductions to human harvests largely irrelevant in the bigger picture.

We have urged the Alaska Board of Fisheries to consider the ramifications of marine mammal predation research in its own deliberations, and to incorporate this information into broader discussions with the state of Alaska or other state/federal governing bodies. We hope this discussion of the issue will provide the general public with a better understanding of the disappointing chinook salmon situation.

Andy Wink is executive director of the Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by the Anchorage Daily News, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary(at)adn.com. Send submissions shorter than 200 words to letters@adn.com or click here to submit via any web browser. Read our full guidelines for letters and commentaries here.

www.timescolonist.com

www.timescolonist.com

www.timescolonist.com

www.timescolonist.com