Sharphooks

Well-Known Member

Did you ever take an outdoor trip where you ended up counting the days for the trip to end, and at the tail end being not only thrilled to have the experience behind you but actually surprised you pulled it off and made it back home in one piece and further still, once back in the safety of your home you make a firm clear-eyed decision never ever to return to that place again?

Well I just walked in the door from one of those trips. Never again.

I first started going to this river in Alaska in 1985 and have never missed a year since. The math tells me that last week was my 40 th year going to this same place.

I go for the wilderness experience and of course, the steelhead fishing which as far as numbers per square meter of river are concerned, is clearly the best steelhead fishing remaining in the Pacific Northwest. It's also the northern-most latitude you can find a steelhead on the West Coast of the Pacific so it's a very unique place.

It has a large winter run that arrives in November. The fish spawn in March and April and this year, there were a huge number of them in the river. There’s an equally large spring run that arrives in March and April and spawns in late May, early June. This year, it was a bit early for the spring fish. There were a few around but not in the large ghostly wads I’m used to seeing. The aggregate run size is anywhere between 4,000 to 15,000 fish, depending on the year. That's a lot of fish in a 19 mile long stretch of river.

The spring-fish are what make me go through all the effort of flying camping gear and my inflatable raft to Alaska then disappearing into the bush for a week long float back down to the Gulf of Alaska.

With the exception of the Russian Far East, I've fished steelhead in pretty much every river system they swim, including the Dean and the Thompson, and I'm here to tell you that the spring fish in this particular Alaskan river, despite the frigid cold water, are every bit as stunning a fighting fish as any of the famous British Columbian steelhead. Pound for pound, they are among the best.

It's not uncommon to lose count of the jumps after 10 of them, one of those special kinds of fish that have you thinking that because your line is down in the tail end of the pool, that must be where the fish is but meanwhile, they're already doing multiple cartwheels in the next hole 100 yards upstream from where you’re standing....you're just starting to figure out that this marvel of a fish you've hooked has taken twice the amount of line off your reel you thought it had and moved through the water so much quicker then you thought a fish could move. Yes, they are that amazing a race of fish.

But conditions have to be just right to catch these spring fish, especially on a swung fly without a float indicator or a big chunk of lead on your leader which is what most of the chuck-n-duck "fly" fishermen use up there. The challenge is to get them on a floating line with no weight. When everything works out with that method, it's like no other steelhead you'll ever hook on any other river you'll fish. They are stone-cold wonders using that method. For me it's always been the fascination of what's difficult and when you get them the difficult way, that’s the fish you’ll be remembering for a decade.

This is what those spring fish look like. I never saw one this year at my feet (after multiple jumps they were all off the hook) but they are stuck like glue in my memory banks from year’s past.

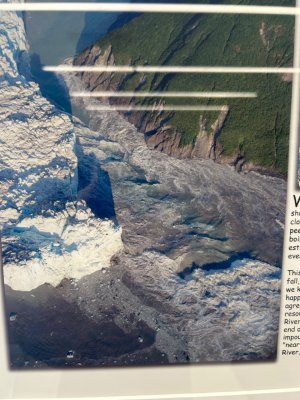

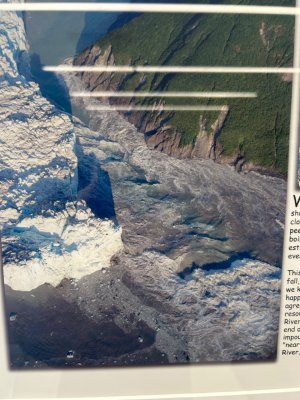

In 1986 and 2002 that river and its amazing steelhead run was almost wiped off the face of the earth. The Hubbard Glacier advanced into an inland fiord and created a moraine dam. In effect, the morain cut off the drainage of Russel Fiord and geologists were predicting that if the morain dam didn't burst, Russel Fiord would eventually overflow its retaining perimeters and cascade down the mountainside wiping out both the lake that feeds this river and the entire river itself— all the riparian bank systems and tributaries that contain and create the holes that produce such marvelous fish habitat; everything….gone in one apocalyptic glacial wave

But in both instances, the glacial moraine dam did burst. This picture captured the moraine dam burst in 2002. It was estimated that the larger wave in the outflow that created that huge shadow at the bottom right of the picture was 50 feet tall.

Great luck that there were geologists up there to capture the event.

Well I just walked in the door from one of those trips. Never again.

I first started going to this river in Alaska in 1985 and have never missed a year since. The math tells me that last week was my 40 th year going to this same place.

I go for the wilderness experience and of course, the steelhead fishing which as far as numbers per square meter of river are concerned, is clearly the best steelhead fishing remaining in the Pacific Northwest. It's also the northern-most latitude you can find a steelhead on the West Coast of the Pacific so it's a very unique place.

It has a large winter run that arrives in November. The fish spawn in March and April and this year, there were a huge number of them in the river. There’s an equally large spring run that arrives in March and April and spawns in late May, early June. This year, it was a bit early for the spring fish. There were a few around but not in the large ghostly wads I’m used to seeing. The aggregate run size is anywhere between 4,000 to 15,000 fish, depending on the year. That's a lot of fish in a 19 mile long stretch of river.

The spring-fish are what make me go through all the effort of flying camping gear and my inflatable raft to Alaska then disappearing into the bush for a week long float back down to the Gulf of Alaska.

With the exception of the Russian Far East, I've fished steelhead in pretty much every river system they swim, including the Dean and the Thompson, and I'm here to tell you that the spring fish in this particular Alaskan river, despite the frigid cold water, are every bit as stunning a fighting fish as any of the famous British Columbian steelhead. Pound for pound, they are among the best.

It's not uncommon to lose count of the jumps after 10 of them, one of those special kinds of fish that have you thinking that because your line is down in the tail end of the pool, that must be where the fish is but meanwhile, they're already doing multiple cartwheels in the next hole 100 yards upstream from where you’re standing....you're just starting to figure out that this marvel of a fish you've hooked has taken twice the amount of line off your reel you thought it had and moved through the water so much quicker then you thought a fish could move. Yes, they are that amazing a race of fish.

But conditions have to be just right to catch these spring fish, especially on a swung fly without a float indicator or a big chunk of lead on your leader which is what most of the chuck-n-duck "fly" fishermen use up there. The challenge is to get them on a floating line with no weight. When everything works out with that method, it's like no other steelhead you'll ever hook on any other river you'll fish. They are stone-cold wonders using that method. For me it's always been the fascination of what's difficult and when you get them the difficult way, that’s the fish you’ll be remembering for a decade.

This is what those spring fish look like. I never saw one this year at my feet (after multiple jumps they were all off the hook) but they are stuck like glue in my memory banks from year’s past.

In 1986 and 2002 that river and its amazing steelhead run was almost wiped off the face of the earth. The Hubbard Glacier advanced into an inland fiord and created a moraine dam. In effect, the morain cut off the drainage of Russel Fiord and geologists were predicting that if the morain dam didn't burst, Russel Fiord would eventually overflow its retaining perimeters and cascade down the mountainside wiping out both the lake that feeds this river and the entire river itself— all the riparian bank systems and tributaries that contain and create the holes that produce such marvelous fish habitat; everything….gone in one apocalyptic glacial wave

But in both instances, the glacial moraine dam did burst. This picture captured the moraine dam burst in 2002. It was estimated that the larger wave in the outflow that created that huge shadow at the bottom right of the picture was 50 feet tall.

Great luck that there were geologists up there to capture the event.

Last edited: