Eric Taylor is a zoology professor at UBC and chairman of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ian Lindsay / Vancouver Sun

The eight Fraser River sockeye spawning populations now

assessed as endangered may never be officially protected by the federal government.

The Cultus Lake sockeye run was deemed endangered in 2003 by a committee of independent scientists, but has still not been officially added to the list of endangered species under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA).

“In practice, most marine fishes that are (commercially) exploited are never listed under SARA, even though many of them are highly endangered,” said Eric Taylor, chairman of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, which advises the federal government.

That is bad news for the Fraser River sockeye.

Eight of the 24 distinct sockeye populations that spawn in the Fraser and its tributaries are now regarded as “endangered” by the committee. Two others are “threatened” and five more are of “special concern”.

But the federal environment minister is under no obligation to protect them.

If the Fraser sockeye — even just the endangered populations — are officially protected under SARA, it becomes illegal to “kill, harm, harass, capture or take an individual” of the species, which would effectively close all Fraser sockeye fisheries until the populations recover, said Taylor, who is a professor of zoology at the University of B.C.

The problem is that the spawning populations deemed endangered enter the river mixed with other commercially sustainable runs.

Federal governments have long exploited a “loophole” in the law that allows the environment minister to avoid officially recognizing species as endangered, by entering an open-ended period of consultation, he said.

In response to a private member’s bill tabled by South Okanagan-West Kootenay MP Dick Cannings, Environment Minister Catherine McKenna has promised to decide whether or not to list species under SARA within nine months of receiving the committee’s recommendations. They will be officially delivered next October.

However, in the case of the Fraser sockeye, the answer could well be no, said Taylor.

“However, just because a species isn’t listed in SARA doesn’t mean good things can’t happen,” he said. “DFO can get involved well before the minister’s decision, and as we saw last year, there was no sockeye fishery at all.”

According to the committee, Fraser sockeye are being harmed by a combination of rising water temperatures — which exhaust the fish as they swim upstream — the pressure of commercial, recreational and First Nations fisheries, and other environmental factors.

The eight populations identified by the committee have experienced significant declines in numbers over three or more generations, said Taylor.

Meanwhile, a

local study published this week in the online journal PLOS One found that 95 per cent of farmed salmon purchased in B.C. supermarkets tested positive for the piscine reovirus (PRV).

According to the authors, PRV was also detected in “37 to 45 per cent of wild salmon from regions highly exposed to salmon farms and five per cent of wild salmon from the regions furthest from salmon farms.”

The study — co-authored by fish farm opponent and independent biologist Alexandra Morton — concludes “that PRV transfer is occurring from farmed Atlantic salmon to wild Pacific salmon, that infection in farmed salmon may be influencing infection rates in wild salmon, and that this may pose a risk of reduced fitness in wild salmon impacting their survival and reproduction.”

The committee doesn’t consider the effect of net-pen fish farms a “smoking gun” in the decline of the sockeye.

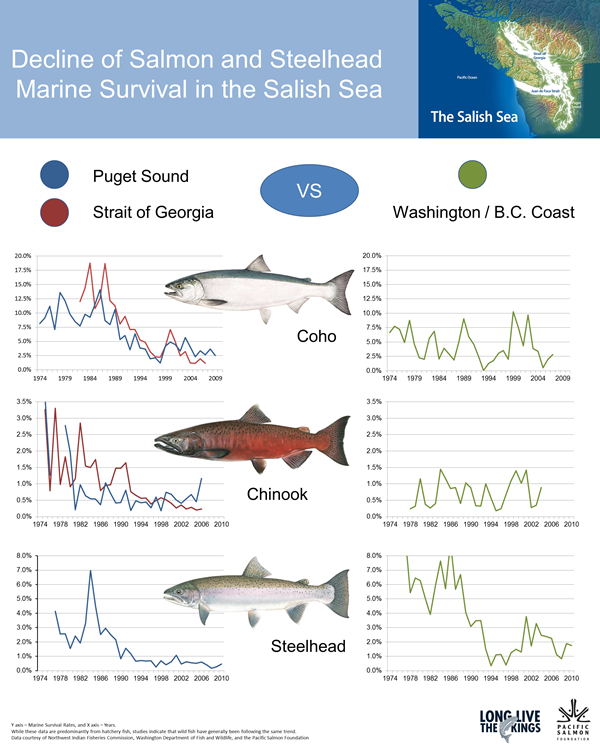

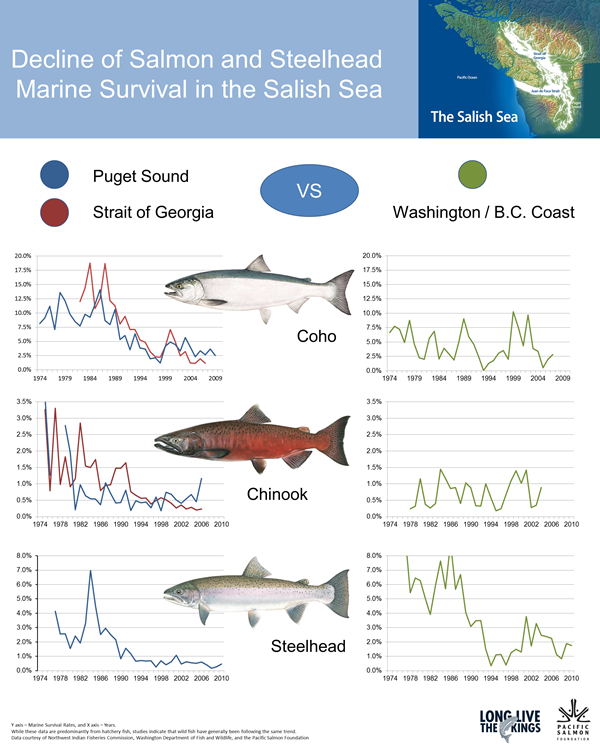

“The evidence that fish farms are a major driver is not clear,” said Taylor. “There is something going on in the ocean, but the greatest decline in survival comes after the fish get … past Vancouver Island.”

Fisheries and Oceans Canada was not able to respond to questions on Thursday.